What if we could unlock the secrets of the human brain to revolutionize how we teach and learn?

A new science of learning is emerging, fueled by converging insights from fields like developmental psychology, machine learning, and neuroscience. This field is uncovering the biological, cognitive, and social factors that influence how we learn, paving the way for more effective teaching practices and improved learning outcomes. For instance, we now understand the importance of active learning, where students are engaged and challenged to construct their own knowledge rather than passively absorbing information. We also recognize the powerful role emotions play in learning. Positive emotions enhance learning while negative emotions like stress can hinder it, highlighting the need for supportive and engaging learning environments. Furthermore, this new science emphasizes the importance of personalized learning, recognizing that each student learns in their own unique way.

Optimizing Learning by Targeting Different Memory Systems

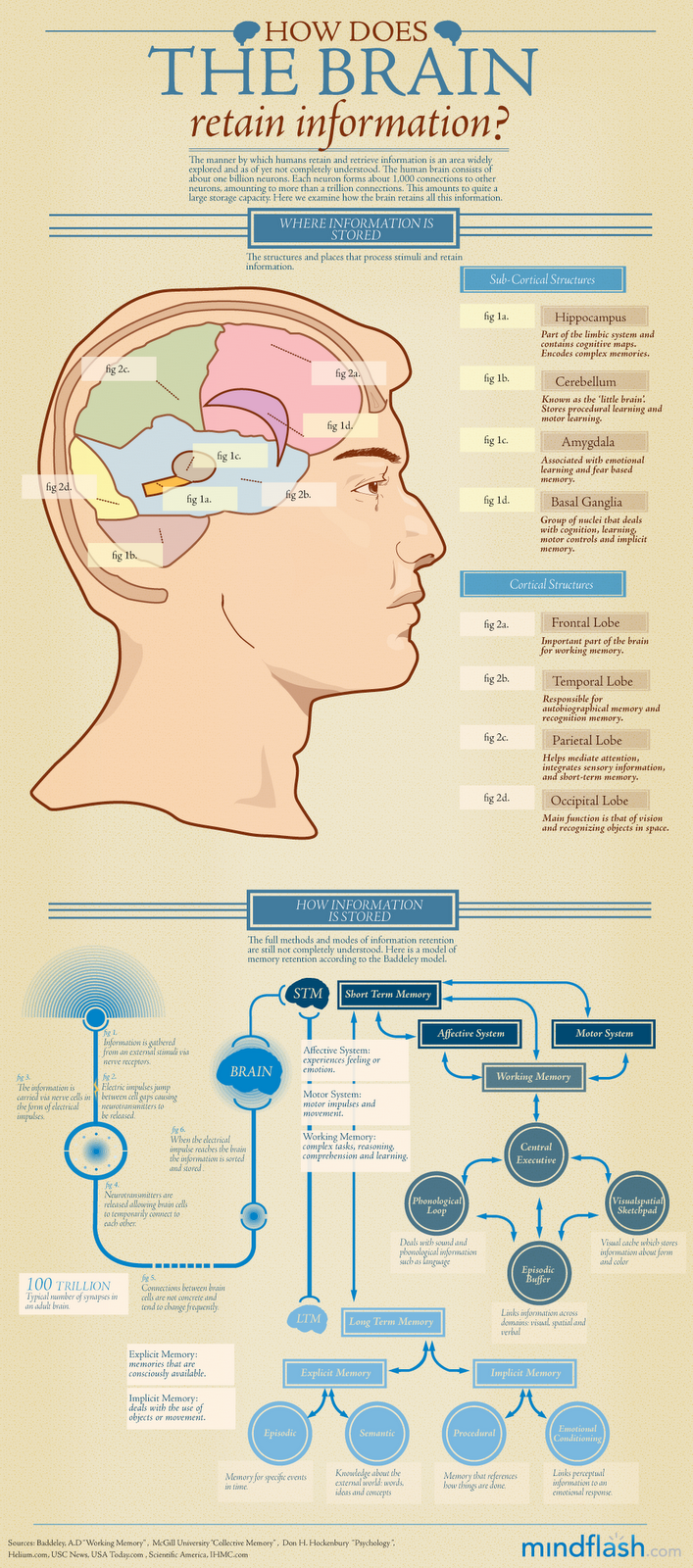

Neuroscience has shown us that memory is more complex than we once thought. It’s not just one thing, but a system of different types, each with its own job and connected to different parts of the brain.

Episodic memory is like a mental scrapbook. It helps us remember past experiences, like a fun school trip or a birthday party. Teachers can tap into this by using techniques that emphasize narrative construction, real-world applications, and the establishment of personal connections with the subject matter.

Semantic memory is our storehouse of facts and concepts. It’s how we remember things like state capitals or the rules of gravity. Teachers can help students build this type of memory by using visuals, diagrams, and clear explanations.

Procedural memory is all about skills. It’s how we learn to ride a bike or play an instrument. To get better at these things, we need practice, feedback, and to learn skills step-by-step.

Understanding these different memory systems can really change how we teach. When teachers know which type of memory is involved in a lesson, they can plan activities that make it easier for students to learn, remember, and use information.

The Adolescent Brain: A Period of Continued Development

Contrary to earlier assumptions, brain development is not confined to childhood. The prefrontal cortex, the brain’s executive control center responsible for planning, decision-making, and impulse inhibition, continues to mature well into early adulthood, typically around 20-25 years of age. This protracted developmental trajectory explains why adolescents often grapple with impulse control, risk assessment, and delaying gratification. They may engage in actions without fully considering the consequences, undertake risks without a complete understanding of potential dangers, or encounter difficulties prioritizing long-term goals over immediate rewards.

This understanding holds significant implications for educators. It underscores the necessity for patience and support as adolescents navigate the complexities of this developmental period. By providing structured environments, clear expectations, and opportunities to cultivate self-regulation techniques such as mindfulness or organizational strategies, educators can facilitate the strengthening of the prefrontal cortex and the development of essential life skills.

Neuroeducation: Bridging Neuroscience and Education

For much of recent history, the fields of neuroscience and education operated in distinct domains, with limited interaction between researchers. However, this began to shift in the 1990s with the growing recognition of the brain’s remarkable plasticity—its capacity to reorganize and adapt throughout the lifespan in response to experiences. This discovery, coupled with advancements in neuroimaging techniques, fueled increasing interest in how insights from neuroscience could inform and enhance educational practices, ultimately leading to the emergence of neuroeducation.

Neuroeducation is an interdisciplinary field that strives to bridge the gap between neuroscience and education. It investigates how the brain learns, remembers, and processes information, and applies these findings to develop more effective pedagogical approaches. By understanding the neural mechanisms underlying learning and cognition, educators can create learning environments that optimize brain function and promote deeper understanding. For instance, incorporating movement breaks into lessons can capitalize on the benefits of physical activity for cognitive function, while integrating mindfulness practices can assist students in managing stress and enhancing focus.

Neuroeducation emphasizes that learning is not a passive process of absorption but rather an active process that induces physical changes in the brain. Every new experience, every acquired skill, every learned fact—all leave their imprint on the brain’s intricate neural networks. This knowledge empowers educators to design learning experiences that leverage the brain’s inherent learning processes. Examples include incorporating spaced repetition into lesson plans to enhance memory consolidation or utilizing storytelling to engage the emotional dimensions of learning.

The goals of neuroeducation are far-reaching. It aims to improve educational outcomes for all learners, address learning challenges and disabilities such as dyslexia or ADHD, promote creativity and innovation in educational settings, and foster a lifelong love of learning. While a relatively nascent field, neuroeducation holds immense potential to transform educational practices and positively impact learners of all ages.

Neuroeducation: Integrating Neuroscience and Artificial Intelligence in Educational Practice

Augmenting the progress of neuroeducation is the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), which presents transformative potential for educational practices. Imagine AI systems functioning as personalized learning guides, identifying each student’s unique learning style, strengths, and areas for improvement. With this insight, AI can create custom-tailored learning plans, perfectly suited to each student’s needs. AI tutors can then step in, providing real-time support, feedback, and challenges that adapt to the student’s progress—keeping them both engaged and motivated. AI-powered games and simulations also turn learning into an immersive experience, designed to match each student’s pace and interests.

AI is also changing how we assess learning. By analyzing work products like essays or problem-solving exercises, AI can pinpoint areas that need further attention and deliver targeted, constructive feedback. It can even assess a learner’s emotional state and engagement during lessons, enabling teachers to adjust their instructional methods for optimal impact.

Looking ahead, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) could allow our brains to interact directly with computers. This technology could be life-changing for students with disabilities, giving them new ways to control devices and communicate. BCIs could also provide real-time feedback on brain activity during learning, helping students improve their focus and self-regulation.

Despite these exciting possibilities, the integration of AI in neuroeducation comes with significant ethical and practical challenges. Protecting student data must be a top priority, necessitating AI systems that are built with privacy at their core. Equitable access to AI tools is also crucial to prevent exacerbating existing achievement gaps. Furthermore, teachers will need comprehensive training to effectively incorporate AI technologies into their classrooms. Striking a balance between technological innovation and human interaction is essential to maintaining the critical role of educators in fostering well-rounded student development.

Curiosity, interest, joy, and motivation—these are the cornerstones of effective learning. Neuroeducation, with its focus on understanding the brain’s role in learning, combined with AI’s innovative potential, offers a path toward a more personalized, engaging, and inclusive educational future.