A brief history of the brain, featuring a few of the major scientists and findings that have contributed to modern neuroscience.

Tag: neuroscience

The Divided Brain

Iain McGilchrist explains how our ‘divided brain’ has profoundly altered human behaviour, culture and society. Taken from a lecture given by Iain McGilchrist as part of the RSA’s free public events programme.

Inside the brain of a buddhist monk

Since 2008, Dr Zoran Josipovic, a research scientist and adjunct professor at New York University, has been placing the minds and bodies of prominent Buddhist figures into a five-tonne (5,000kg) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine. He says he has been peering into the brains of monks while they meditate in an attempt to understand how their brains reorganise themselves during the exercise.

“Meditation research, particularly in the last 10 years or so, has shown to be very promising because it points to an ability of the brain to change and optimise in a way we didn’t know previously was possible.”

Dr Josipovic’s research is part of a larger effort better to understand what scientists have dubbed the default network in the brain. He says the brain appears to be organised into two networks: the extrinsic network and the intrinsic, or default, network.

The extrinsic portion of the brain becomes active when individuals are focused on external tasks, like playing sports or pouring a cup of coffee. The default network churns when people reflect on matters that involve themselves and their emotions. But the networks are rarely fully active at the same time. And like a seesaw, when one rises, the other one dips down. This neural set-up allows individuals to concentrate more easily on one task at any given time, without being consumed by distractions like daydreaming.

“What we’re trying to do is basically track the changes in the networks in the brain as the person shifts between these modes of attention,” Dr Josipovic says.

Dr Josipovic has found that some Buddhist monks and other experienced meditators have the ability to keep both neural networks active at the same time during meditation – that is to say, they have found a way to lift both sides of the seesaw simultaneously. And Dr Josipovic believes this ability to churn both the internal and external networks in the brain concurrently may lead the monks to experience a harmonious feeling of oneness with their environment.

Read more on this story at BBC Health

Why do we have brains?

Neuroscientist Daniel Wolpert starts from a surprising premise: the brain evolved, not to think or feel, but to control movement. In this entertaining, data-rich talk he gives us a glimpse into how the brain creates the grace and agility of human motion.

Opening a window into the movies in our minds

In research, that brings to mind the movie Minority Report, a group of neuroscientists have found a way to see through another person’s eyes.

By reconstructing YouTube videos from viewers’ brain activity, researchers from UC Berkeley, have, in the words of Professor Jack Gallant, opened ” a window into the movies in our minds.”

Gallant’s coauthors of the study, published in Current Biology, watched YouTube videos inside a magnetic resonance imaging machine for several hours at a time. The team then used the brain imaging data to develop a computer model that matched features of the videos — like colors, shapes and movements — with patterns of brain activity. Subtle changes in blood flow to visual areas of the brain, measured by functional MRI, predicted what was on the screen at the time.

Lead author, Shinji Nishimoto, said the results of the study shed light on how the brain understands and processes visual experiences. The next line of research is to investigate if the technology could one day allow people who are paralyzed to control their environment by imagining sequences of movements.

Is the mind modular?

Mind – n. the human consciousness that originates in the brain and is manifested especially in thought, perception, emotion, will, memory, and imagination.

Architecture of the human mind

No robot can solve a crossword, or engage in a conversation, with anything like the facility the average human being can. Somehow or other we humans are capable of performing complex cognitive tasks with minimal effort. Trying to understand how this could be is the central explanatory problem of the discipline known as cognitive psychology. There is an old but ongoing debate among cognitive psychologists concerning the architecture of the human mind.

The ‘general-purpose problem-solver’ mind

According to one view the human mind is a’ general-purpose problem-solver’. This means that the mind contains a general set of problem-solving skills or ‘general intelligence’ which it applies to an infinitely large number of different tasks. So the same set of cognitive capacities is employed, whether you are trying to count marbles, deciding what movie to see, or learning a foreign language – these tasks represent different applications of the human’s general intelligence.

The modular mind

A rival view argues that the human mind contains a number of subsystems or modules – each of which is designed to perform a very limited number of tasks and cannot do anything else. This is known as the modularity of mind hypothesis. So for example it is widely believed that there is special module for learning a language – a view deriving from the linguist Noam Chomsky. Chomsky insisted that a child does not learn to speak by overhearing adult conversation and then using ‘general intelligence’ to figure out the rules of the language being spoken; rather there is a distinct neuronal circuit – a module – which specialises in language acquisition in every human child which operates automatically and whose sole function is to enable that child to learn a language, given appropriate prompting. The fact that even those with very low ‘general intelligence’ can often learn to speak perfectly well strengthens this view.

Clues from the broken brain

Some of the most compelling evidence for the modularity of mind hypothesis comes from studies of patients with brain damage. If the human mind were a general all-purpose problem-solver we would expect damage to the brain to affect all cognitive capacities more or less equally. But this is not what we find. On the contrary, brain damage often impairs some cognitive capacities but leaves other untouched. A good example of this is damage to a part of the brain known as Wernicke’s area – following injury or viral infection – which leaves a patient unable to understand speech although they are still able to produce fluent, grammatical sentences. This strongly suggests that there are separate modules for sentence production and comprehension. Other brain-damaged patients lose their long-term memory (amnesia) but their short-term memory and their ability to speak and understand are entirely unimpaired.

Modular or ‘general purpose problem-solver’ …or both?

The evidence for a modular mind is compelling and the philosopher Jerry Fodor published a book in 1983 titled The Modularity of Mind which explained exactly what a module is. However the modular view is controversial and is not endorsed by all philosophers. Opponents argue that even in a general purpose problem-solver brain it is still possible that distinct cognitive capacities might be differently affected by brain damage. Fodor himself even admits that the answer may not be all that clear cut and suggests that while perception and language are modular, thinking and reasoning are almost certainly not – we solve some cognitive tasks using specialised modules and others using our ‘general intelligence’. However not all psychologists agree with this.

Is the mind scientifically inexplicable?

Exactly how many modules there are and precisely what they do, are questions that cannot be answered given the current state of brain research. Most neuroscientists equate mind and brain as one and the same thing and predict that in the not-too-distant future neuroscience will deliver a radically different type of brain science, with radically different explanatory techniques what will explain the architecture of the human mind.

The Human Brain: How We Decide

Take a virtual tour of the human brain as it makes decisions

When love is the drug

Dr Paul Zak, a neuroeconomist, investigates the neurophysiology of economic decisions. His research at the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies draws on economic theory, experimental economics, neuroscience, endocrinology, and psychology to develop a comprehensive understanding of human decisions.

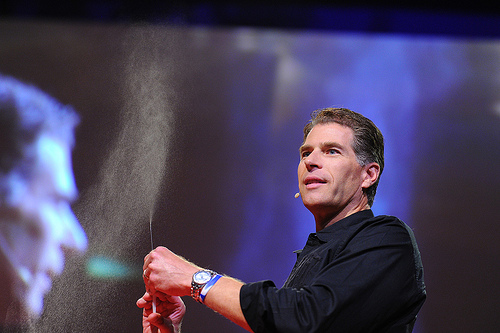

Dr Zak also studies why we humans like and trust each other. And the answer, he’s found, is the compound oxytocin. In this photo above, Zak has brought a syringe loaded with oxytocin onstage, to create a striking visual aid by atomizing it into the air (now that’s what I call a prop!)

Oxytocin – the cuddle chemical – is a hormone made in the hypothalamus – a structure at the base of the brain involved in regulating strong emotions. Research has shown that behaviours necessary for developing long-term relationships such as hugging, kissing and skin-to-skin contact – trigger the release of this hormone into the blood and as the romantic attachment increases so does the amount of oxytocin circulating in the body. In fact, it is suggested that this hormone ‘primes’ the brain to fall in love by acting on the brain to increase trust and reduce fear, increase empathy and generosity and increase attachment and bonding. For this reason oxytocin is sometimes called the cuddle chemical. Some drug companies have considered putting oxytocin into perfumes and sprays – to help attract a mate.

Yes folks …it’s official… love is a drug!

Weekly Round Up

Studies looking at the brains of people playing a fairness game found very different responses between Buddhist meditators and other participants.

It’s possible that depression could be cured by reducing mild swelling in your brain.

New York University neuroscientists have identified the parts of the brain we use to remember the timing of events within an episode. The study, which appears in the latest issue of the journal Science, enhances our understanding of how memories are processed and provides a potential roadmap for addressing memory-related afflictions.

A leading University of Chicago researcher on empathy is launching a project to understand psychopathy by studying criminals in prisons.

A new study at the University of California at Davis has made progress in determining the factors that affect brain degeneration and why our brains shrink with age and a new drug to prevent the development of Alzheimer’s disease could be tested on patients within six years according to researchers at Lancaster University.

Is the search for the cause of autism a hall of mirrors?

The ‘broken mirror’ theory is a popular theory in autism research but it seems that all is not as it appears as a high-profile paper in Neuron reports that people with autism do not have trouble understanding others’ actions or intentions or even imitating those actions1.

Monkey see, monkey do.

Mirror neurons were discovered by neuroscientists in the 90’s while recording the activity of nerve cells or neurons in the brains of monkeys where it was noticed that certain neurons remain silent when the monkeys observe other monkeys performing the same action2 – hence the name mirror neuron.

Scientists have extended this finding in the human brain to show that nerve activity in mirror neurons also remain silent when observing another person performing an action and/or expressing an emotion3 and this silence is not observed in people with autism – hence the ‘broken mirror’ theory of autism.

Getting it “write”

However in a 2007 study 25 children with autism were compared with non-autistic ‘controls’ on several goal-directed imitation (mirror) tasks shown to activate regions of the brain believed to contain mirror neurons4. In one experiment, the children sat at a table and were asked to copy an adult as she touched a pattern of dots on the tabletop. The study showed that normal healthy children make typical errors on this task – for instance copying the adult’s goal but using the wrong hand. The children with autism made exactly the same error, meaning that they selectively imitate the goal of the action and both groups show the same pattern of brain activity in brain regions believed to contain mirror neurons. These findings suggest that there is nothing wrong with basic mirror systems in people with autism.

Hall of mirrors

Part of the problem may be that the ‘broken mirror’ theory relies on several unsupported assumptions: that the mirror system is responsible for understanding goals and imitation, that goal understanding and imitation are abnormal in autism, and that these deficits cause the social difficulties seen in autism.

It’s all about connections

One possible explanation is that the mirror neuron system itself could be normal in autism, but its projections, or the brain regions it is projecting to, could be abnormal instead. Also, the mixed findings could be due to the broad spread of the autism spectrum disorders.

References: