The entertainment world was recently shaken by the tragic passing of Matthew Perry, the beloved actor best known for his role as Chandler Bing on the iconic sitcom “Friends.” Perry’s death, linked to a ketamine overdose, has cast a spotlight on this complex drug, its therapeutic potential, and its inherent dangers. In this post, we’ll explore ketamine’s effects on the brain, its promise in mental health treatment, and the critical need for responsible use and regulation.

Ketamine: A Brief Overview

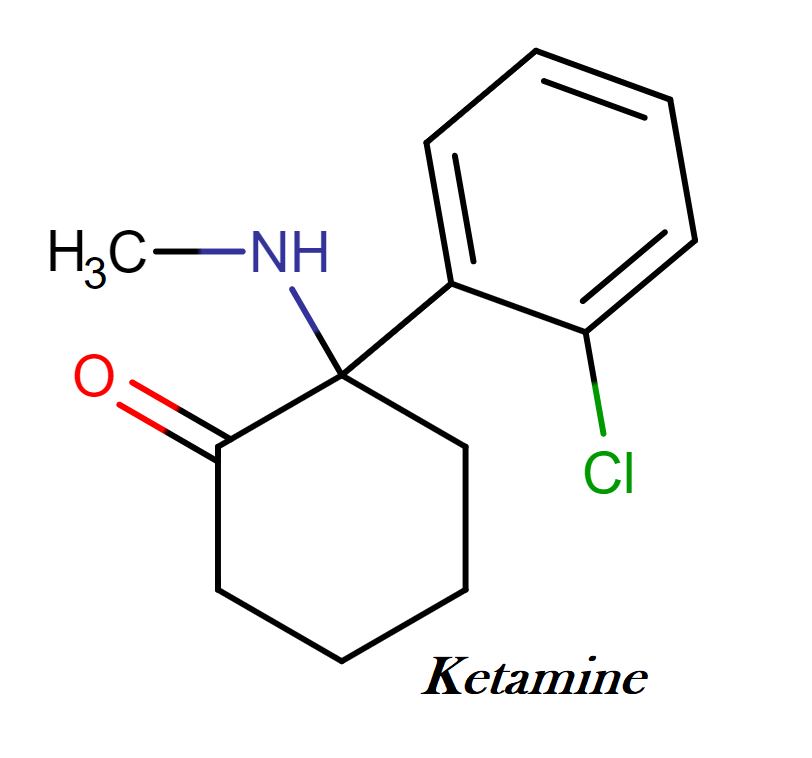

Ketamine, first synthesized in 1962, has a long history as an anesthetic and analgesic. During the late 1960s, ketamine was marketed as the dissociative (out-of-body experience) anesthetic, under the name Ketalar and was used to treat soldiers in the Vietnam War. The abuse potential of ketamine was recognized in the early 1970s, but reports of ketamine abuse in human and veterinary medicine did not appear until the early 1980s in Australia and in the early 1990s in the United States. In recent years, it has gained significant attention for its rapid antidepressant effects, particularly in cases of treatment-resistant depression. Ketamine’s primary mechanism of action involves blocking the NMDA receptor for glutamate in the brain, leading to a dissociative state and a cascade of neurochemical changes.

Ketamine’s Impact on the Brain

Findings from my own laboratory in 1997 showed that repeated ketamine intake alters the balance between the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin in the brain. Ketamine’s interaction with the NMDA receptor for glutamate triggers a surge in glutamate, a neurotransmitter vital for learning and memory. This glutamate surge is thought to promote the growth of new synapses and neural connections, particularly in brain regions associated with mood regulation. Additionally, ketamine disrupts the default mode network (DMN), a brain network linked to rumination and self-referential thinking, which may contribute to its antidepressant effects. Research also suggests that ketamine may stimulate neurogenesis (the growth of new neurons) and promote neuroplasticity (changes in neural connections).

Ketamine’s Impact on the Mind

Ketamine’s psychological actions have been characterized as similar to temporary schizophrenia. Healthy volunteers receiving ketamine in an experiment have experienced sensations reminiscent of LSD. Ketamine can prompt people to feel like they are becoming transparent, blending into nearby individuals, or becoming an animal or object. Users may feel like their bodies are transforming into harder or softer substances. Persons may think they remember experiences from a past life. Some users take the drug to enter a semi-paralytic state described as similar to near-death experiences in which people perceive their consciousness as floating above their bodies, sometimes accompanied by meaningful hallucinations and by insights about the user’s life and its proper place in the cosmos.

The Promise of Ketamine in Mental Health

When administered at a therapeutic dose ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effects have revolutionized the field of mental health treatment. Studies have shown that a single therapeutic dose of ketamine can alleviate depressive symptoms within hours, offering hope to individuals who have not responded to traditional antidepressants. In fact, so effective is therapeutic ketamine that it has been proposed as a chemical replacement for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and it may eventually replace the need for ECT altogether. Beyond depression, ketamine is being investigated for its potential in treating anxiety disorders, PTSD, and addiction.

The Perils of Ketamine

While ketamine holds immense therapeutic promise, it is crucial to acknowledge its risks. Ketamine can cause dissociative effects, hallucinations, and other adverse reactions. Moreover, it has a potential for abuse and addiction, as tragically illustrated by Matthew Perry’s case. Long-term effects of ketamine use on brain function and cognition remain an area of ongoing research.

Lessons from the Death of Matthew Perry

Matthew Perry’s untimely death serves as a poignant reminder of the dangers of substance abuse, even with substances that have therapeutic potential. It underscores the critical need for responsible use, careful monitoring, and effective regulation of ketamine.