If you read my post yesterday on the neuroscience of success, you will have read of the unbeatable combination of optimism tempered with reality. Having written that post, it was fascinating today to read a paper in the current edition of Science Translational Medicine, which shows that a patient’s belief that a drug will not work can indeed become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If you read my post yesterday on the neuroscience of success, you will have read of the unbeatable combination of optimism tempered with reality. Having written that post, it was fascinating today to read a paper in the current edition of Science Translational Medicine, which shows that a patient’s belief that a drug will not work can indeed become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Researchers from Oxford University identified the regions of the brain which are affected in an experiment where they applied heat to the legs of 22 patients, who were asked to report the level of pain on a scale of one to 100. The patients were also attached to an intravenous drip so drugs could be administered secretly.

The initial average pain rating was 66. Patients were then given a potent painkiller, remifentanil, without their knowledge and the pain score went down to 55.

They were then told they were being given a painkiller and the score went down to 39.

Then, without changing the dose, the patients were then told the painkiller had been withdrawn and to expect pain, and the score went up to 64.

So even though the patients were being given remifentanil, they were reporting the same level of pain as when they were getting no drugs at all.

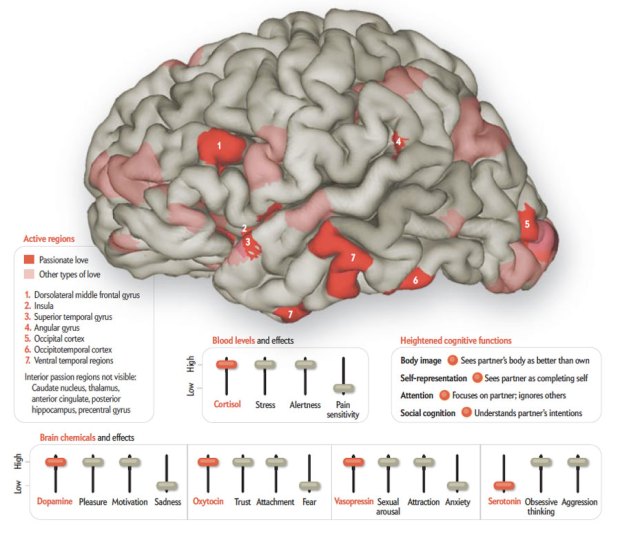

Brain scans during the experiment also showed which regions of the brain were affected. The expectation of positive treatment was associated with activity in the cingulo-frontal and subcortical brain areas while the negative expectation led to increased activity in the hippocampus and the medial frontal cortex.

The limbic system comprises several cortical and subcortical brain areas that are interconnected. This system essentially controls emotions, and the autonomic and endocrine responses associated with emotions. The hippocampus also belongs to the limbic system and plays an important role in long-term memory. Activity in the medial frontal cortex predicts learning from errors.

This latest research could have important consequences for patient care and for testing new drugs. Negative expectations about a drug can reduce its efficacy quite significantly, as indeed positive expectation can boost its efficacy. So it seems, that once more, a positive attitude holds the key to another area of success!